The renewed enthusiasm over the past few years for phonics instruction has been heartening. I have believed in, and therefore taught, phonics skills since the beginning of my teaching career in 1970. (In fact, I am the proud owner of a well-worn 1967 edition of A Guide to Teaching Phonics, by June Orton.) Phonemic awareness and basic phonics skills are essential foundations on which students build toward the ultimate goal of reading: comprehension. So, through the phonics wars and beyond I continued to teach phonics to my students (and I still do today). In addition, I've been working steadily with our team at Read Naturally to enhance and expand Read Naturally's phonics programs and to plan for more improvements and additions!

The renewed enthusiasm over the past few years for phonics instruction has been heartening. I have believed in, and therefore taught, phonics skills since the beginning of my teaching career in 1970. (In fact, I am the proud owner of a well-worn 1967 edition of A Guide to Teaching Phonics, by June Orton.) Phonemic awareness and basic phonics skills are essential foundations on which students build toward the ultimate goal of reading: comprehension. So, through the phonics wars and beyond I continued to teach phonics to my students (and I still do today). In addition, I've been working steadily with our team at Read Naturally to enhance and expand Read Naturally's phonics programs and to plan for more improvements and additions!

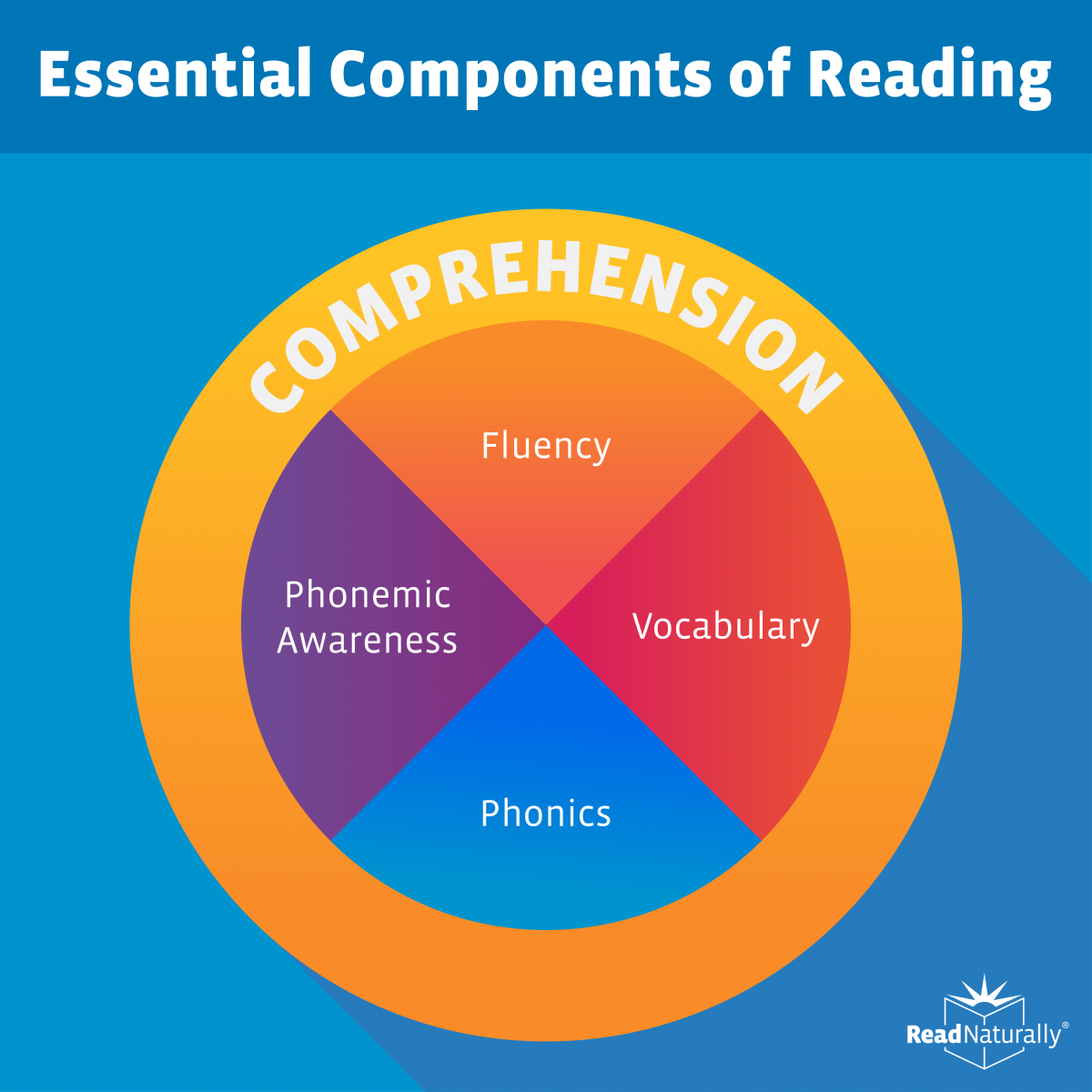

The increased attention on phonics of late has inspired many valuable conversations. Some questions I've been getting relate to how best to teach phonics and how teachers can learn enough about phonics themselves to teach it. Some teachers have even asked if they should spend all their reading time teaching phonics. Is phonics hugely important? Yes. Is it the only thing we need to teach? No. Phonics is a significant piece of a bigger puzzle.

I spent the majority of my teaching career as a special education teacher, Title I teacher, or reading specialist. For over 50 years, I have worked with thousands of students with a wide range of abilities and challenges—and personalities! Each student I have taught has also taught me. Among the many lessons, one very general one is that reading is a complex skill. Few human beings can naturally pick up the skill of reading without instruction. Yet learning does come naturally to the vast majority of us, and most students can indeed learn to read with appropriate instruction and practice.

Some of the main things I have found effective for helping students tackle the often daunting task of learning to read are these:

- Use the main processes we use to learn almost anything: model/teach the skill, promote frequent, quality practice of it, and monitor progress.

- Attend to all five components of reading (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension) as appropriate based on where students are in their development—often layered with one another and over time in changing proportions.

- To the extent possible, treat students as individuals who often require different instruction and support.

1. Use the main processes we use to learn new skills.

Think about the many things you have learned to do well: maybe tying your shoes, swimming, or making an omelet. Did you listen to, watch, and/or receive clear instruction from someone who had already mastered the skill? Did you practice the skill over and over again? Did you notice yourself or have someone tell you what parts you are doing well and what parts you could improve? Employing these basic strategies for learning—modeling and instruction, practice, and progress monitoring—allow people to learn to do many things, including reading. That’s why these strategies are the foundation on which Read Naturally programs are built. Regardless of the curriculum you’re using, keep in mind that in order to master a skill as complex as reading, students will need modeling and guidance, repetition, and the self-knowledge and motivation that come with assessing performance.

2. Attend to all five components of reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

2. Attend to all five components of reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

Phonemic awareness and basic phonics skills are essential foundations on which students build toward the ultimate goal of reading—to make sense of text—to comprehend it. Within that statement it is clear that solid phonemic awareness and phonics instruction and support is only the beginning. As students progress in their reading skills they need to develop their fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension skills too. The earliest readers will need to spend the most time on the most basic skills of phonemic awareness and phonics. Then once they grasp and begin to master the basics of decoding, more and more time must shift to more advanced components of reading.

Note that the essential components of reading can often receive concurrent attention, with certain components getting more of the focus depending on the reader's needs. Even very early readers get some initial lessons in more advanced components like vocabulary and comprehension as they listen to an adult read a story fluently, as they discuss that story and ask questions about words they didn't understand. Ideally, students learn decoding skills, master those skills through practice, and then become automatic at reading isolated words and connected text. As they become automatic and accurate readers, they will be able to focus on the meaning of words, sentences, and passages because they no longer need to spend so much mental energy on decoding. Teachers should spend time on all the components of reading as they teach—just in appropriate ratios for the students' reading development—and sometimes adjusted a bit according to their temperaments. This is why teaching reading is also an art.

3. To the extent possible, differentiate instruction.

It's difficult to talk about what is appropriate for students in part because of how different what is appropriate can be from one student to another. Teachers usually have multiple students to teach at a time—and meeting each student's needs can seem impossible. Many times students will all get the same lessons and those lessons won't be tailored to best help each student. However, there are often things teachers can do to make sure students get at least some customized support. The goal of addressing the various needs of individual students is behind the flexible design of most Read Naturally programs. It can be a bit overwhelming for teachers to acquaint themselves with all of the customization Read Naturally programs facilitate, but there can be a big payoff in student progress. Here is a blog post Read Naturally teacher trainer Claire Hayes wrote about the ways to customize the Read Live program.

If this all seems complicated, that’s because it is! As previously stated, reading is a skill—and it takes a lot of effort to teach it well. Plus, English is a complex language, full of rules—and exceptions to those rules! If you are unsure of all of the phonics rules and feel overwhelmed by the prospect of teaching them to your students, you’re not alone. Thankfully, there are many resources out there to help you. I recommend reading the work of David Kilpatrick. In addition, Read Naturally’s GATE program has scripted lessons that are great for students' learning but also can help teachers at the same time. Similarly, our Word Warm-ups Live program delivers scripted phonics lessons, explaining these complicated rules in student-friendly ways and giving students opportunities to practice applying the rules using a motivating process.

If this all seems complicated, that’s because it is! As previously stated, reading is a skill—and it takes a lot of effort to teach it well. Plus, English is a complex language, full of rules—and exceptions to those rules! If you are unsure of all of the phonics rules and feel overwhelmed by the prospect of teaching them to your students, you’re not alone. Thankfully, there are many resources out there to help you. I recommend reading the work of David Kilpatrick. In addition, Read Naturally’s GATE program has scripted lessons that are great for students' learning but also can help teachers at the same time. Similarly, our Word Warm-ups Live program delivers scripted phonics lessons, explaining these complicated rules in student-friendly ways and giving students opportunities to practice applying the rules using a motivating process.

As 2022 comes to a close, I find myself feeling grateful that phonics instruction is finding its way back into a well-deserved prominent place in more reading curricula. I am also hopeful that as many students as possible will receive increasing support, having their individual needs met and ultimately becoming proficient in all aspects of reading. That’s a big dream, and there's much work to do in the attempt to achieve it (which is probably why I haven’t retired yet!). Reading teachers, you have a challenging and essential job. We at Read Naturally see you and are here to support you. I hope you all enjoy a well-deserved winter break.

Share your student’s success story—nominate him or her for our Star of the Month award. Win a Barnes & Noble gift card for the student and a Read Naturally gift certificate for your class!

Share your student’s success story—nominate him or her for our Star of the Month award. Win a Barnes & Noble gift card for the student and a Read Naturally gift certificate for your class!

Do you have a phonics program using CD's and worksheets?